Teaching

I am an experienced and dedicated teacher—driven by the question of what makes literary studies meaningful in the twenty-first century.

At UC Berkeley, Johns Hopkins, and elsewhere I have designed and taught courses across a range of periods and fields, including seminars on the global eighteenth century, Romantic literature and its reception, and (post) colonial literature and history. I have also taught composition courses on topics ranging from contemporary fiction to political cinema, and, at Mount Tamalpais College, introductions to lyric poetry for incarcerated people. This experience has taught me to facilitate conversation among students of diverse academic and social backgrounds. It has also reinforced my commitment, in the classroom and on the page, to enabling active and thoughtful social engagement through humanistic inquiry.

Scroll down for more information on courses I have taught, including syllabi and lessons plans, as well as a statement of my teaching philosophy.

The 18th Century

Race, Gender, Enlightenment

Description

This course is a study in the literature of the long eighteenth century with a specific focus on topics of gender, race and ethnicity, and literary form. As a seminar on criticism, students will develop their skills in close reading and analytical writing by engaging key texts written in Britain and France from 1680 to 1790. As they do so, students will consider the various forms through which authors of this period address social and material inequality—drama, short fiction, the novel, letters, and memoir—and the many modes in which this writing occurs: satire, realism, speculative fiction, and life writing.

Authors and texts include: Eliza Haywood, Fantomina; Daniel Defoe, Roxana; John Gay, Polly; Samuel Johnson, Rasselas; Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, The Turkish Embassy Letters; Oladuah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative; and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Confessions.

Uneven Enlightenment

Description

This course is a study in the “enlightenment” as a concept and historical period from the eighteenth century to the present, with a specific focus on innovations in philosophical and literary writing between the years 1680 and 1800. Students will read from a handful of key texts written in Britain, France, and the United States that address issues of inequality, nationality, and governance. As they read this material, they will bear in mind a peculiar contradiction. On one hand, the years 1680 to 1800 were key to the formation of human rights, democratic politics, and religious tolerance. On the other hand, they entailed genocide and mass destruction through transatlantic slavery and (settler) colonialism in the Americas, the Caribbean, and South Asia. Students in this course will ask how writers of the enlightenment address this contradiction (if at all), and what legacies of the enlightenment are visible today.

Authors and artists include: Daniel Defoe, Moll Flanders; Jonathan Swift, A Modest Proposal; William Hogarth, “Marriage A-la-Mode” and other works; Phillis Wheatley Peters, selected poems; and Jane Johnston Schoolcraft, selected poems.

Click here for the lesson plan: “Judging a Book by Its Cover”

The Romantic Era

Inventing Romanticism

Description

The aims of this course are twofold: first, to familiarize students with major works by writers of the British Romantic period—including Jane Austen, John Keats, William Wordsworth, William Blake, and Percy and Mary Shelley—and, second, to introduce students to the reception of these works by literary critics in the twentieth and twenty-first century whose writings represent a range of interpretive positions: deconstructive, new historicist, feminist, postcolonial, and others. This is an advanced research seminar. As such, students will devote considerable time to crafting research projects, including formulating and sharing research questions, developing a bibliography, and drafting a 20-page paper in consultation with your peers and instructor. To help familiarize students with professional research, a significant portion of time in class will be spent analyzing scholarship on the Romantic period, assessing different critical approaches and testing the arguments of critics against the primary literature they discuss.

Authors and texts include: Wordsworth, “Tintern Abbey” and selected poems; William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience; Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn” and selected poems; Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice; Mary Shelley, Frankenstein.

Romanticism and the British New Left

Description

This course explores the history of Romantic literature written in English between 1780 and 1830, and the importance of this literature to historical and theoretical scholarship from the 1960s onward associated with the New Left movement in Britain. This course has two aims. The first is to consider how poets and novelists of the Romantic period addressed major historical events of their time. Here we will pay specific attention to the rise of industrial capitalism and rural enclosures. The second aim is to introduce students to the work of predominantly Marxist historians and cultural theorists of the postwar period for whom the Romantic era is of special importance. This includes, among others, E.P. Thompson, Raymond Williams, and Stuart Hall. As a seminar on criticism, students will consider the methodological aims—as well as blind spots—of Marxist criticism from this period.

Primary authors and texts include: William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience; William Godwin, Caleb Williams; Mary Wollstonecraft, Letters Written From Sweden, Norway, and Denmark; selected poems by Mary Robinson, John Clare, and Jane Johnston Schoolcraft; M. NourbSe Philip, Zong!

Secondary authors and texts include: E.P. Thompson, from The Making of the English Working Class; Raymond Williams, from Marxism and Literature; and Stuart Hall, “Race, the Floating Signifier.”

The Scientific Imagination

Description

For scholars of literature, music, and the visual arts, the years between 1780 and 1830 are known as the Romantic Era. For historians of science this same period is known as “the second Scientific Revolution.” Alongside innovations in the arts, the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century witnessed the formation, or radical transformation, of several fields of scientific inquiry: biology, chemistry, anthropology, botany, geology, and climatology among them. In this course we examine how these changing fields shaped and influenced each other. We will ask how new discoveries in the world of science inspired novelists and poets; and how the work of novelists and poets, in turn, inspired scientists, shaping the questions they asked of the world.

Authors include: Goethe, Elective Affinities; Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner; Erasmus Darwin, The Botanic Garden; and Humphry Davy, Consolations in Travel.

Literature in the Age of Revolutions, 1780-1830

Description

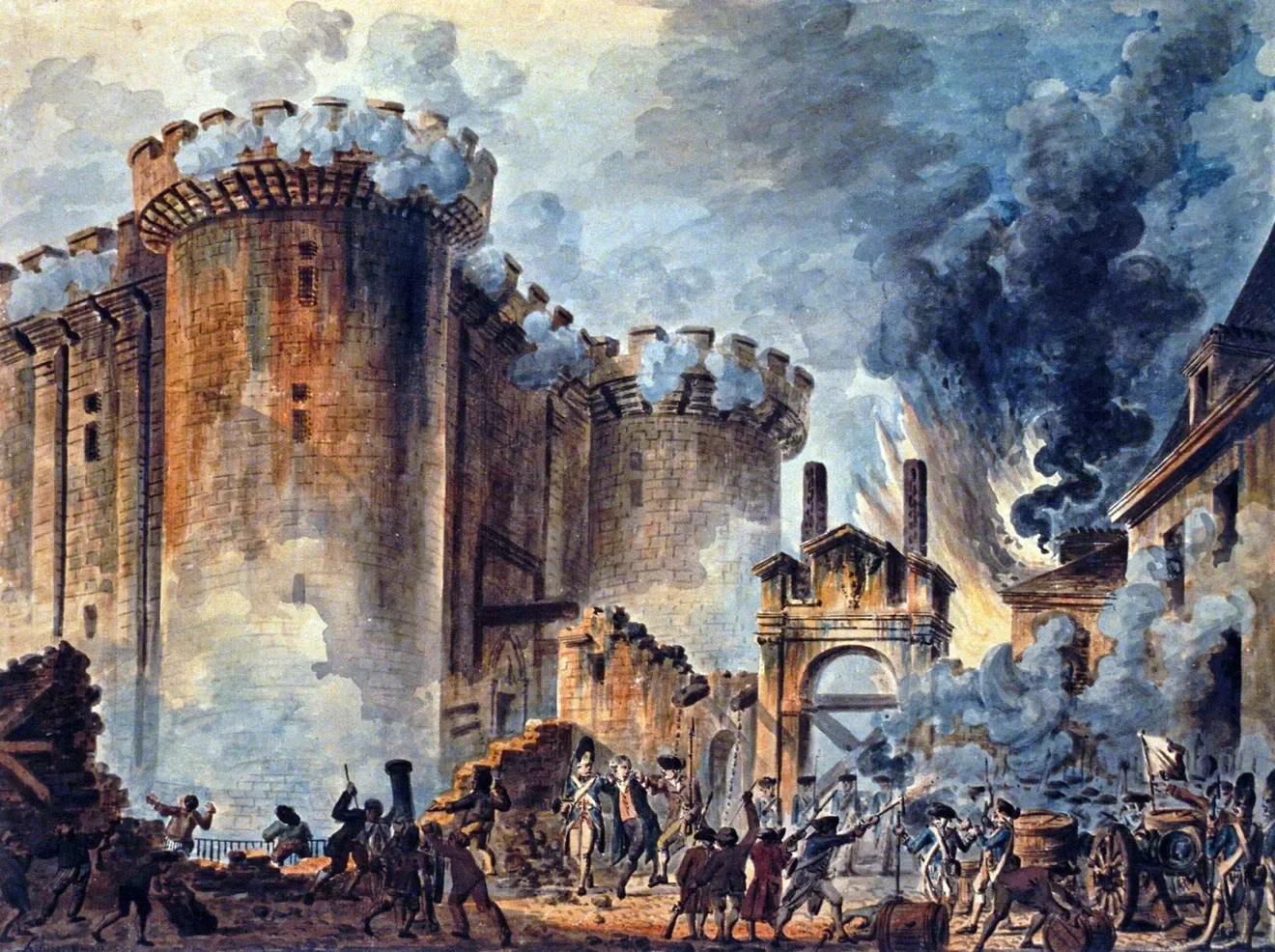

This course explores literary, philosophical, and political writing from the years 1780 to 1830. Commonly known as the Romantic era, this tumultuous half-century profoundly shaped the politics, economics, and social organization of the modern world. The course is divided into three units. We begin with the Industrial Revolution. Here our focus will be on the experiences of enclosure and urbanization. We will ask how life was altered in both the “country” and the “city,” and how those alterations were recorded in poetry and prose of the time. In units two and three our concern will be on two of the most significant overthrows of state power in modern history: the French and Haitian Revolutions. Examining letters, poems, and narrative accounts from Haiti and France, as well as Britain, we will explore not only what happened in these revolutions, but what it felt like to live through them, at home and abroad.

Authors and texts include include: Maria Edgeworth, Castle Rackrent; William Blake, America: A Prophecy; Maximilien Robespierre, “On the Trial of the King”; Helen Maria Williams, Letters Written in France; Toussaint L’Overture, selected writings; Leonora Sansay, The Secret History.

Colonial and Postcolonial Literary History

Genres of Empire

Description

In this course, students will examine the historical and theoretical intersections between aesthetic form and the empires of Europe, from the Spanish conquest of the Americas to twentieth-century decolonization. Students will consider how different genres—drama, prose fiction, and film—both challenge and promote the establishment of empires in Europe, the Americas, and beyond.

The course is divided into three units, each organized around a different genre. The first considers William Shakespeare’s The Tempest alongside historical writings from the sixteenth-century colonization of the Americas, including by Bartolomé de Las Casas and eyewitness accounts from the Indigenous Azteca peoples. The second unit considers popular Victorian fiction by Rudyard Kipling and H. Ridder Haggard in light of the British Empire’s consolidation of power in India and Africa. And the final unit examines twentieth-century filmmakers, Gillo Pontecorvo, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Sarah Maldoror, and Steve McQueen, as they represent struggles for political independence in Algeria, Cuba, Angola, and Northern Ireland.

Romance as Colonial History

Description

This course is a study in the history of romance as a mode, genre, and concept from the Middle Ages to the Romantic era. Students will attend closely to the formal and thematic characteristics of romance in its initial phases, including its origins as a form of vernacular storytelling, as well as the extent to which those characteristics are thought to shape innovative poetry and prose fiction of the early modern period and beyond. This course will also pay special attention to the political contexts in which romance develops and to which it imaginatively responds; students will ask what role romance plays in the formation of ideologies of empire, race, and religious otherness, both within Europe and between Europe and the Middle East. A major focus in this regard will be on histories of settler colonialism.

Authors and texts include: Geoffrey of Monmouth, History of the Kings of Britain; Torquato Tasso, Gerusalemme liberata; Aphra Behn, Ooronoko; Lord Byron, The Corsair; and Charles Brockden Brown, Edgar Huntly; or Memoirs of a Sleep-Walker.

Cross-period Literary and Visual culture

Archaism in Literature and new media

Description

This seminar explores archaism as a central practice of European aesthetic culture. It considers poets, philosophers, and filmmakers from the eighteenth century to the present whose work imitates or otherwise invokes outdated forms of cultural expression. Students will encounter well-known archaists like Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as well as contemporary poets and experimental artists such as Caroline Bergvall, Anne Carson, and Pier Paolo Pasolini, among others. To better appreciate and understand these many writers—separated by centuries and political orientations—students will also engage a handful of theoretical writings that take up questions of nostalgia, desire, backwardness, and the meaning and value of history. We will ask what it means to be “untimely,” in Friedrich Nietzsche’s terms, and how that untimeliness endorses or disrupts normative claims of belonging—to identities, communities, and modes of thought.

Poetry, Politics, and Society

Description

This is a reading and composition course for incarcerated students at Mount Tamalpais College, formerly the Prison University Project at San Quentin State Prison. It provides an introduction to modern English-language poetry, especially that which concerns itself with problems in contemporary society, including racial discrimination, class exploitation, and war. We will ask how poetry deals with these problems and in what ways reading poetry can help us understand our place in the world today.

Throughout the course, our emphasis will be on close reading. We will attend carefully to the form, language, and meaning of each poem we read. We will also focus on the fundamentals of analytical writing. Through in-class discussion and essay assignments, we will learn not only how to read poetry, but how to write about poetry in clear and persuasive language.

Authors include: William Blake, W.B. Yeats, W.H. Auden, Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, Seamus Heaney, Claudia Rankine

Statement of Teaching Philosophy

What can literature do? In response to this question, the feminist and existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir answered: “Literature’s good fortune is that it allows us to communicate in what separates us. Literature—if it is authentic—is a way of surpassing the separation by affirming it.” For de Beauvoir, literature allows us to reflect on our “situation,” the many factors, including racial, gender, and class identities that shape our orientation to the world. But literature also lets us recognize the situation of those around us. When we read, de Beauvoir suggests, we affirm who we are, never eliding or forgetting our identity, while engaging with those with whom we collectively inhabit this world. “That is the miracle of literature,” de Beauvoir writes, “a truth that is other becomes mine without ceasing to be an other.” Through literature we surpass our differences, but only, paradoxically, by affirming them.

De Beauvoir’s belief in the necessity of literature to a just and open world underwrites my commitment as an instructor of undergraduate and non-traditional students: adult transfers, working parents, and the incarcerated. To admit of a multitude of experiences and forms of life is to address a reality in which lives are differently recognized and unevenly cared for. Each situation has its own history, its own vulnerabilities. Acknowledging this fact lies at the core of my teaching practice, which strives to not only foster a welcoming and inclusive environment for the exchange of ideas; nor only to assign writers from an array of social, racial, and religious backgrounds; but also to help students see how their own beliefs and suppositions shape the way they act—or, as de Beauvoir would put it, “engage”—in the world.

Facilitating conversation and critical engagement through literature can be a difficult task, particularly among students whose interests lie outside the humanities or whose access to higher education has been impeded by the demands of work and family life. My approach in the classroom therefore encourages balanced attention to the form of literature alongside its context. Through patient and deliberative reading, I help students recognize how their own conceptions of modern life are often anticipated, even complicated, in texts that might feel too difficult or distant to warrant their attention.

I have developed my approach across several institutions, including most recently the University of California, Berkeley, and Mount Tamalpais College, formerly the Prison University Project at San Quentin State Prison. At Mount Tamalpais, I taught poetry of various historical and cultural traditions. In Fall 2021, my course “Poetry, Politics, and Society” asked students to imagine poetry as a testament to the complexities of human social and political life. One day, while addressing the topic of poetic sound, my students were discussing “Sonny’s Lettah,” a poem from the Jamaican-born British artist Linton Kwesi Johnson on anti-Black police violence in London, together with Jane Johnston Schoolcraft’s “Lines Written at Castle Island, Lake Superior,” a Romantic-era poem written in Schoolcraft’s native Ojibwe language. Although apparently incommensurate, these poems—separated by language, national tradition, and nearly two centuries—reflect the similar ways that poetry uses dialect and the ballad form to record experiences of political injustice. Our discussion was centered on how oral traditions resurface in modern poetry to register protest. But we gradually began to talk about the persistence of white violence against Black and brown peoples, from the first settlement of Europeans in the Americas to the present. As students began to disclose their experiences with and conceptions of racism, my practice as a teacher was challenged by the forceful presence of real suffering in the classroom. The result was an appreciation of poetry’s capacity to resonate powerfully and to generate difficult, though necessary, conversations.

I am still learning to understand how literature inspires and confronts my students; how it gives them a way to think through the world and aspire to change it. I am eager to continue learning, and to bring my expertise to students whose variety of thought and identity will be enhanced by encountering literature in the classroom. Whether as the instructor of a composition course or an advanced undergraduate seminar, my goal is the same: to help students appreciate not only their own situation, nor only those of others, but a world in which all of us must live and act.